Jerome Powell needs to look in the mirror.

During a recent interview aired on 60 Minutes, the Federal Reserve chairman said it was time to have an “adult conversation” about the national debt and conceded that the U.S. government is on “an unsustainable fiscal path.”

Powell said, “We're effectively borrowing from future generations,” and that it is time for us to put a priority on “fiscal sustainability. And sooner's better than later.”

Powell is right. A $34 trillion debt growing by the day is unsustainable. The U.S. government is already paying more to service the national debt than it is on national defense. But just as he’s done with price inflation, Powell fails to recognize his own culpability.

The Fed chair talks a good game. Open-mouth operations are his specialty. But he could do something about it because the Federal Reserve is a huge part of the problem. In fact, it enables the borrowing and spending.

In an interview on Kitco News, Fox Business “Making Money” host Charles Payne called Powell out on his hypocrisy, characterizing it as “a nice soundbite.”

But the function of the Federal Reserve itself belies what he was saying. They've always been the biggest buyers of U.S. Treasuries, which facilitate this crazy nonstop spending on both sides of the political aisle. …

We're here at the precipice of this situation where he rightfully acknowledges that there's a problem, but to be quite frank, I don't see the Federal Reserve doing anything about it. They play a role in all of this. They're not backing away from this role.

How the Fed Backstops the Federal Government’s Spending Addiction

The Biden administration is spending money at an astonishing clip. Every month, the federal government blows through half a trillion dollars on average.

This leads to massive monthly budget shortfalls. That means the U.S. Treasury has to borrow money month after month to cover the deficits.

The U.S. government borrows money by issuing Treasury notes and bonds. Banks and other financial institutions around the world buy Treasuries at auctions. After an allotted amount of time (anywhere between a few months to 30 years), they get their money back plus interest.

Banks and financial institutions hold some Treasuries on their balance sheets and sell others on the open market. For instance, a bank may buy a bunch of Treasuries, hold them until the price goes up, and then sell them to other investors for a small profit.

The investment community considers U.S. Treasuries one of the safest investments on the market. Although they offer a relatively low rate, most people assume the U.S. government will never default.

This makes U.S. bonds a popular investment vehicle, and the Treasury can issue a lot of them. But bonds are subject to economic laws of supply and demand.

If the government issues too many, the price falls, and the yield (interest rate) the government pays will increase. Higher interest rates mean bigger profits for investors, incentivizing more buyers to enter the market.

But as I’ve already mentioned, rising rates pose a problem for the U.S. government. They push interest expenses relentlessly higher. This theoretically puts a cap on borrowing since interest expense can only rise so high and remain sustainable.

This is where the Federal Reserve steps in.

As the government floods the market with bonds, there simply isn’t enough investor demand to sustain the borrowing, so the Fed eases the supply pressure.

With an operation called quantitative easing (QE), the Fed creates artificial demand for bonds in the marketplace and holds interest rates artificially low. This allows the U.S. Treasury to issue more bonds than it otherwise could at a lower interest cost.

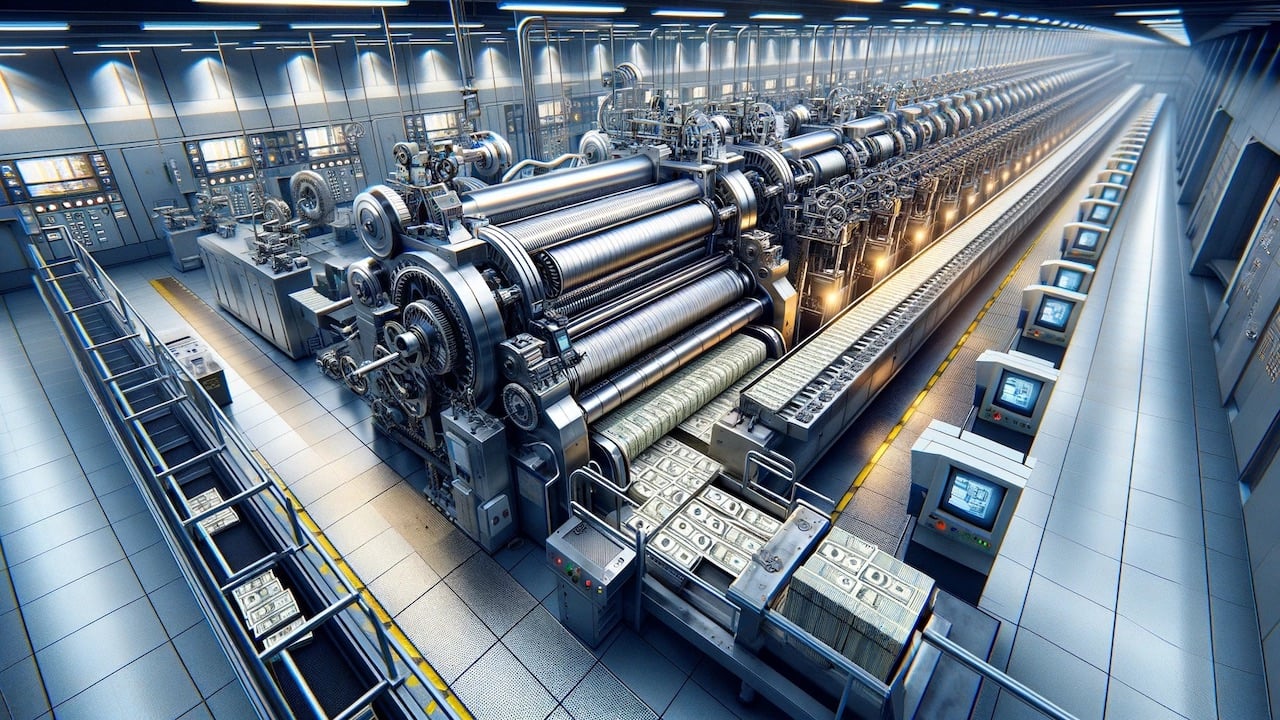

And how does the Fed pay for these bonds?

By printing money.

The central bank doesn’t literally print $100 bills in the basement of the Eccles Building, but the effect is the same. The Fed creates digital money, sends it to the seller, takes possession of the bonds, and then holds the Treasuries on its balance sheet. This process is called “debt monetization.”

As Payne alludes, the Fed is a significant player in the bond market, particularly during a crisis.

For instance, during the Great Recession, the U.S. government ran trillion-dollar deficits for the first time. To facilitate deficit spending, the Fed expanded its balance sheet by more than $4 trillion.

It ran a similar operation during the pandemic. In effect, the Fed monetized every dollar borrowed in 2020.

Theoretically, the Fed only holds these bonds temporarily. At some point, it sells the bonds back into the market, soaking up the excess money it created. When Ben Bernanke launched the first round of quantitative easing in 2008, he swore it wasn’t debt monetization. He said it was an emergency measure that would be unwound.

You’ll be shocked to learn it was never unwound. Between 2008 and 2021, the Fed added $8 trillion to its balance sheet, injecting an equivalent amount of new money into the U.S. economy.

This is the status quo. The Fed must frequently intervene. Without the central bank’s big fat thumb on the market, bond prices would tank, and interest rates would skyrocket. This is a simple function of supply and demand.

With the U.S. government on a massive spending spree and borrowing billions every month, there are simply too many Treasuries being issued for the market to absorb. The Federal Reserve has to stand at the ready to backstop U.S. government borrowing.

Even when the Fed isn’t running QE, it typically continues buying Treasuries to hold its balance sheet at a steady level. As bonds mature, the Fed buys new Treasuries to replace them, keeping its thumb on the market. The only time the Fed shrinks its balance sheet is when price inflation gets too hot.

The Fed tried to decrease the amount of bonds on its balance sheet in 2018 but quickly abandoned the mission when the stock market crashed, and the economy got shaky.

The central bank is currently running quantitative tightening, but even if it followed through with its plan, it would take about six more years for the Fed to shed all the bonds it bought during the pandemic. And there are plenty of indications that the Fed will abandon tightening in the very near future.

It will have to in order to support the government's spending habits.

Powell has a lot of nerve lecturing about the debt problem. He is the pusher who supplies the drugs that keep the spending addicts in D.C. high.

About the Author:

Mike Maharrey is a journalist and market analyst for MoneyMetals.com with over a decade of experience in precious metals. He holds a BS in accounting from the University of Kentucky and a BA in journalism from the University of South Florida.