The Federal Reserve’s bank bailout program shut down on March 11.

So, what next?

The Fed created the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) after the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank last March. The program was set up so banks could easily access cash “to help assure banks have the ability to meet the needs of all their depositors."

The bailout was a sweetheart deal for banks, and it effectively papered over the banking crisis caused by rising interest rates.

How Did This Bank Bailout Work?

Through the BTFP, banks, savings associations, credit unions, and other eligible depository institutions were able to take out short-term loans (up to one year) using U.S. Treasuries, agency debt, mortgage-backed securities, and other qualifying assets as collateral.

Instead of valuing these collateral assets at their market value, banks were able to borrow against them “at par” (Face value).

Why was this a sweetheart deal?

Well, imagine that a flood damaged your house. Do you think a bank would loan you money based on the value of your home before the flood without any repairs?

Of course not.

In fact, the bank probably wouldn’t loan you money using a damaged house as collateral at all.

Banks don’t accept collateral that is worth less than the amount of the loan. But that’s exactly what the Fed did for struggling banks with significantly devalued loan portfolios due to rising interest rates.

Rising rates and a tanking bond portfolio were the icebergs that sank Silicon Valley Bank.

SVB went under because it tried to sell its undervalued bonds to raise cash. The plan was to sell the longer-term, lower-interest-rate bonds and reinvest the money into shorter-duration bonds with a higher yield. Instead, the sale dented the bank’s balance sheet with a $1.8 billion loss driving worried depositors to pull funds out of the bank.

The BTFP gave banks facing similar problems an alternative. They could quickly raise capital against their bond portfolios without realizing big losses in an outright sale. It gave banks a way out, or at least the opportunity to kick the can down the road for a year.

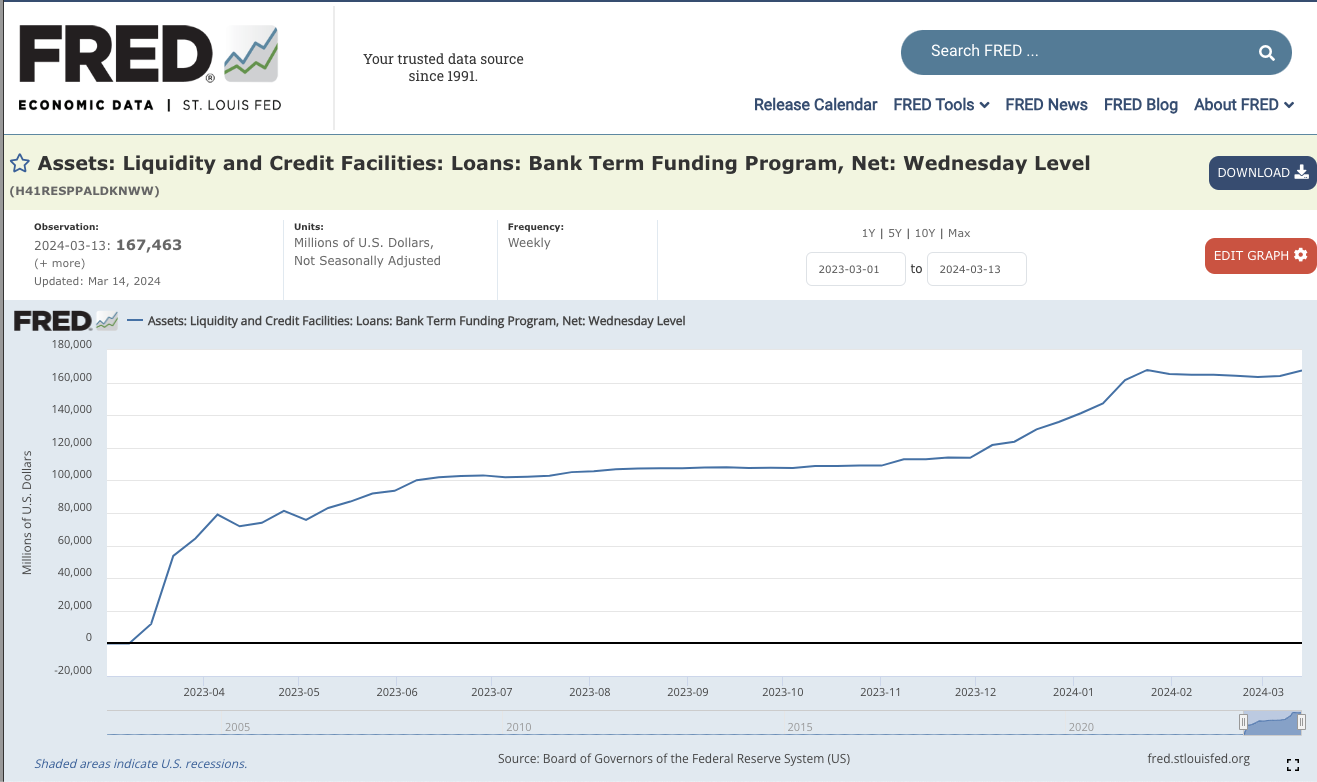

As one would expect, the balance in the BTFP surged initially as banks tapped into the bailout. But borrowing never stopped.

In the first week, banks borrowed $11.9 billion from the program, along with more than $300 billion from the already-established Fed Discount Window. By April 5, the balance in the BTFP rose to just over $79 billion. By June, banks had borrowed around $100 billion. Borrowing plateaued before taking off again in November. The balance in the BTFP grew by nearly $58 billion between the end of November and late January, peaking at $167.8 billion.

Why did the program see a sudden surge in borrowing late last fall?

Well, the Fed inadvertently provided a second sweetheart deal through the BTFP by offering loans at a lower interest rate than the Federal Reserve was paying on reserves it held on behalf of banks. This created a profitable arbitrage opportunity.

For example, the Fed charged a 4.93 percent interest rate on a BTFP loan as of Jan. 23. At the same time, the central bank was paying 5.4 percent on reserves. This allowed banks to earn nearly 50 basis points by borrowing money from the bailout and then depositing it in their reserve account at the Fed.

As you can see from the chart, BTFP borrowing suddenly stopped after the Fed closed this loophole in late January.

In fact, the balance in the BTFP dropped for several weeks, but then suddenly jumped again during the last week of the program's operation. Banks borrowed over $3.4 billion during that final week. Given there was no arbitrage opportunity, this last-minute surge of borrowing was almost certainly driven by troubled banks taking advantage of one last opportunity for a bailout.

What Happens Without the Bailout?

There is some speculation that the end of the BTFP could lead to another wave of bank failures.

A recent Fortune article said the end of this “emergency funding crutch” couldn’t have come at a worse time for small banks.

A year after the failure of Silicon Valley Bank, nothing in the banking system has fundamentally changed. Unrealized losses on U.S. banks’ books dropped in the fourth quarter of 2023, but they still came in at $478 billion, a historically high level. Interest rates remain high. And with sticky price inflation, it seems likely that the Federal Reserve will have to keep rates higher for longer.

Meanwhile, the commercial real estate (CRE) market is a ticking time bomb.

The CRE sector faces the triple whammy of falling prices, falling demand, and rising interest rates. The post-pandemic rise of telecommuting and work-at-home programs crushed demand for office space. Vacancy rates in commercial buildings have soared.

Small and midsized regional banks hold a significant share of commercial real estate debt. They carry more than 4.4 times the exposure to CRE loans than major “too big to fail” banks. According to an analysis by Citigroup, regional and local banks hold 70 percent of all commercial real estate loans.

The Fortune article said for banks with high CRE exposure, “the timing couldn’t have been worse” for the end of the BTFP.

“A wave of maturities for 10-year loans signed after the Great Recession is on the horizon. Some $930 billion of U.S. commercial real estate debt, or around 20% of the estimated $4.7 trillion in total CRE mortgage debt outstanding, will mature in 2024, according to Mortgage Bankers Association estimates. That means banks will have to refinance, extend, or pay off these loans.

“The situation is so bad that Scott Rechler, cofounder and CEO of the real estate giant RXR, told Fortune that CRE’s issues, coupled with banks’ ongoing problems, could reduce the number of banks in the U.S. by '500 or more' over the next two years as lenders fail and industry consolidation continues.”

Troubled banks still have an option – the Federal Reserve’s discount window. This is considered a “lender of last resort” for the banking system. However, banks are generally reluctant to utilize the program because it sends a clear signal that the bank is in trouble. It also lacks the sweetheart deal the BTFP offered.

According to the Fortune article, the end of the BTFP isn’t likely to send the banking sector into freefall.

“But it is more bad news on top of an already ugly landscape for an industry that’s hurting nationwide.”

Keep an eye on the banking sector moving forward. A financial crisis may have been bubbling under the surface for the last year. The Fed managed to plug one hole in the dam with this bailout program. But with the BTFP a thing of the past, we could start to see more leaks and cracks. It will be especially interesting to see what happens as the loans come due. (Banks had one year to pay back BTFP loans.)

About the Author:

Mike Maharrey is a journalist and market analyst for MoneyMetals.com with over a decade of experience in precious metals. He holds a BS in accounting from the University of Kentucky and a BA in journalism from the University of South Florida.